The Theological Dimension of the Thought of M. Fethullah Gülen (Part 1)

In This Article

-

This paper concentrates on the theological dimension of Gülen’s thought that underlies his role as spiritual director and teacher of internalized Islamic virtue.

-

Fethullah Gülen’s most important model and teacher is the Prophet Muhammad himself.

-

Gülen holds that the sunna (Prophet’s actions, words, and things he approved) was God’s gift to Muslims so that they would know how to live according to God’s will in a way pleasing to the Creator.

Gülen as Spiritual Master

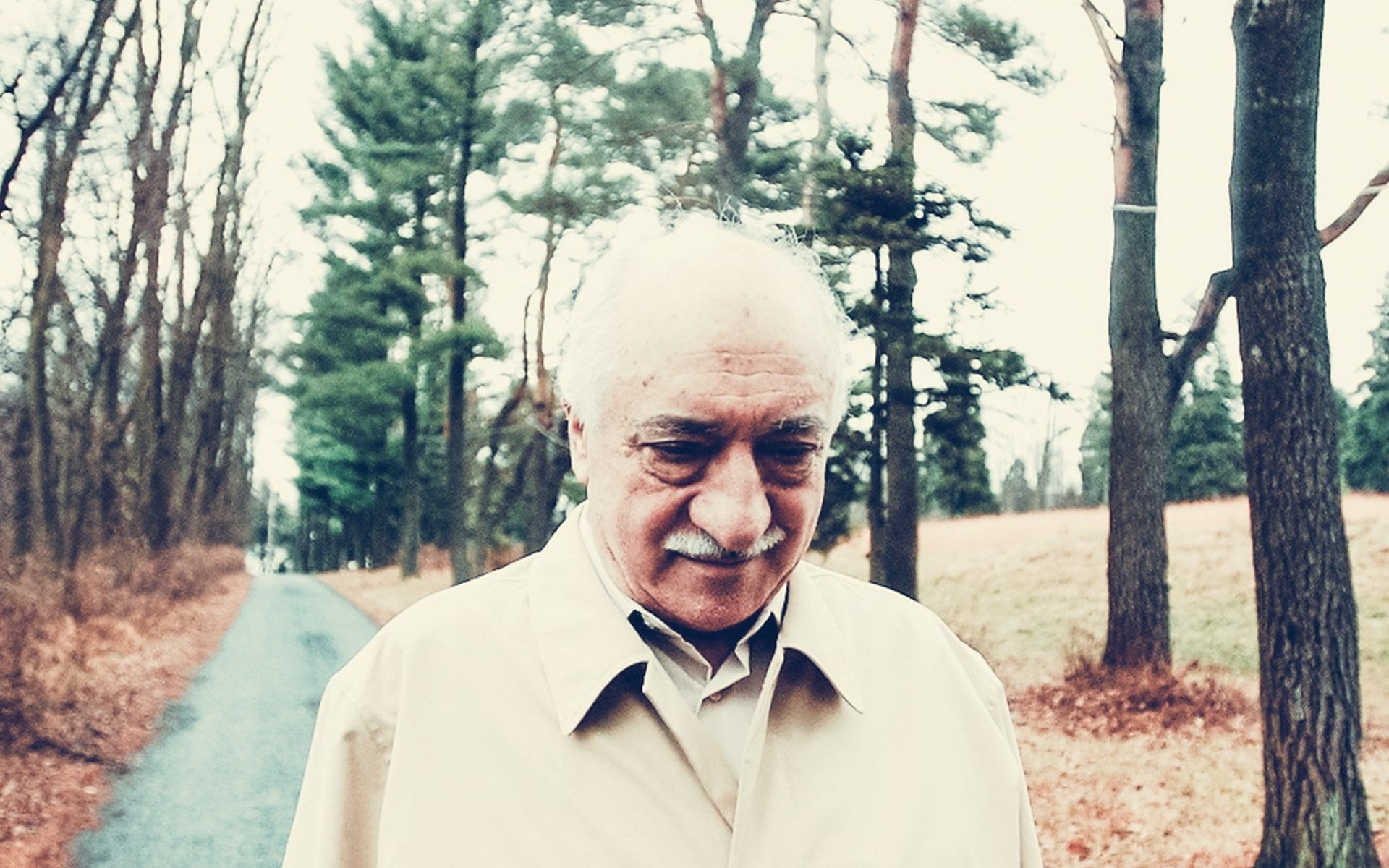

In recent years, much has been written about the thought of Fethullah Gülen and the activities of the “Gülen community” [1] from diverse perspectives. Some have focused on his pedagogical principles and methods in an effort to understand the success of the schools and other educational ventures founded and administered by those in the community associated with Gülen’s name. Others have analyzed the social programs and institutions inspired by his ideas. Still others have focused on Gülen’s vision as the philosophical motor behind a social movement that is working to produce social change and renewal in Turkey, in the worldwide Islamic umma, or in modern societies in general. Others have underlined Gülen’s call for universal love, fellowship, and tolerance and consequently his encouragement of interreligious dialogue as an essentially Islamic obligation.

In this paper, I will concentrate on the theological dimension of Gülen’s thought that underlies his role as spiritual director and teacher of internalized Islamic virtue. I will attempt to look at the specific understanding of Islamic faith that Gülen communicates to the young scholars and teachers, businessmen, and householders who make up the community formed by his vision. It is this theological perspective that guides Gülen’s role as spiritual master whose counsel has guided individual Muslims and formed a coherent and workable community life among his disciples. It may well prove in the long run to be the area of his deepest and most enduring influence.

Roots in Qur’an and Sunna

Every religious tradition, whether we are speaking of Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, or others, provides a wealth of doctrinal teaching, theological reflection, and spiritual experience so vast that it goes beyond what any individual believer, including the theologian, is able to integrate personally and hand on to others. Even the greatest scholar or mystic is able to assimilate, build upon, and communicate only a relatively small part of the whole tradition. This means that every religious teacher is constantly making choices, selecting some elements of the scriptural and communitarian tradition upon which to comment, elaborate, and emphasize while passing over other elements in silence.

Since no one can communicate the whole of tradition, an individual thinker’s choices reveal much about that person’s own theology and spirituality. In the case of Fethullah Gülen, it is not surprising that his most important model and teacher is the Prophet Muhammad himself. His teaching is not so much natural philosophy as it is commentary on the Qur’an and hadith. Gülen’s “prophetology” holds that although it is possible to arrive at a certain limited knowledge of God by reason, particularly by means of reflection on nature, much of human existence can only be known through prophetic revelation. He writes,

“Although we can find God by reflecting upon natural phenomena, we need a Prophet to learn why we were created, where we came from, where we are going, and how to worship our Creator properly. God sent Prophets to teach their people the meaning of creation and the truth of things, to unveil the mysteries behind historical and natural events, and to inform us of our relationship, and that of Divine Scriptures, with the universe.” [2]

On this basis, it is not surprising that the vast majority of Gülen’s references are to the teaching of the Qur’an and his practical examples taken from the sunna of the Prophet. Gülen holds that the sunna (Prophet’s actions, words, and things he approved) was God’s gift to Muslims so that they would know how to live according to God’s will in a way pleasing to the Creator. “The sunna, the unique example set by the Messenger of God for all Muslims to follow, shows us how to bring our lives into agreement with God’s commands and obtain His good pleasure” [3]. Moreover, the sunna is the source for the humane qualities that Gülen as a spiritual guide wants to instill. Character traits such as tolerance, piety, forgiveness, and peacemaking are rooted in the divine teachings proclaimed by, and exemplified in, the life of the prophets, particularly Muhammad. For example, in speaking of tolerance, Gülen notes that the quality is not of human origin but is derived from prophetic teaching. “Tolerance is not something that was invented by us. Tolerance was first introduced on this earth by the prophets whose teacher was God” [4].

Forbearers in the Islamic tradition

The emphasis that Gülen places on the Qur’an and sunna underlines the “orthodox” nature of Gülen’s teaching and the community’s practice. Some observers of the movement have asked whether Gülen’s theology is to be located within the mainstream of Islamic doctrine. If it is true, as many scholars hold, that there is more than a single mainstream of Islamic theology and practice, into which current does Fethullah Gülen fit? This question can perhaps best be answered by looking at those Muslim scholars and pious forbearers with whom Gülen can be seen to identify himself.

Gülen’s writings are replete with references to the words of earlier Muslim scholars and mystics. He frequently cites those whom he calls “the lovers,” [5] that is, predecessors as Jalal al-Din Rumi, Yunus Emre, Ahmad Yasawi, and Said Nursi. All of these figures are more or less associated with the Sufi tradition. Rumi [6] and Yasawi were poets and founders of tariqas (spiritual orders), and Yunus Emre was a wandering folk poet not associated with any tariqa. Moreover, those ulama to whom Gülen refers, such as Ghazali, Junayd, and Shah Waliullah, are scholars who have close connections to the broader Sufi tradition. Even among those modern figures whom Gülen holds up as “heroes of thought and action” he includes Sufis and Sufi-oriented writers like Ahmet Hilmi, Ferid Kam, and Necip Fazıl Kısakürek [7].

Gülen’s theology can be located best in this broad “humanistic current” of Muslims who stress the interior dispositions to be fostered in the believer in response to the revealed Qur’anic message and in imitation of the prophetic example found in the sunna. In this interpretation of Islam, faith is “virtue-oriented”; these Muslims stress internal qualities such as sincerity, patience, peace, tolerance, forgiveness, compassion, respect for others, and acceptance of differences, and encourage humble lives characterized by deeds of goodness, love, and service.

This current, while closely related to the Sufi tradition, antedates Sufism as such and finds its origins in the pious, ascetic community of early Muslims centered in the Madina Mosque who came to be called the ahl al-suffa. These early scholars eschewed commercial and military pursuits and devoted their lives to studying and teaching the religious usul (sources). Rıfat Atay [8] sees Gülen as reviving the ancient tradition of the suffa in two ways, firstly by embodying in his own life four of the typical characteristics of the early phenomenon (single, simple, humble, and pious), and secondly, by carrying on a consistent pattern of spiritual and theological formation for a select number of dedicated students.

Gülen’s relationship to the Sufi tradition

The suffa movement can be seen as a “pre-Sufi phenomenon, a precursor of tendencies that later developed into Sufism. While the similarities of the modern “Gülen movement” with the early ahl al-suffa are undeniably strong, the question remains of Gülen’s relation to historical Sufism. Zeki Saritoprak has called Gülen “a Sufi in his own way” [9]. Employing a term coined by Fazlur Rahman, I have referred to Gülen, and to Said Nursi before him, as “neo-Sufis” [10]. Mustafa Gökçek notes that Gülen did not begin to write about Sufism until the 1990s, when he was over 50 years old [11]. His earlier sermons and writings focused mainly on basic elements of Islamic faith and moral prescriptions, although he often included examples from the lives of earlier Muslim mystics and ascetics. However, in 1990, Gülen began to include a brief insert in the magazine Sızıntı that in each monthly issue elaborated a different concept of Sufi terminology. These articles became the basis for Gülen’s masterwork, Key Concepts in the Practice of Sufism: Emerald Hills of the Heart, of which four volumes have now been published in English [12].

The twentieth-century scholar Said Nursi would seem to provide the closest model for Gülen’s personal relationship to Sufism. Nursi, while showing respect for the Sufi tradition and affirming many of their insights, always distinguished himself from the Sufis. Nursi distinguished his theological method from that of the Sufis by means of his praxis-oriented approach, what he called the “way of reality,” in which he abstained from contemplative speculation in favor of practical guidance for his disciples’ individual and communitarian lives. He states: “However, since our way is not the Sufi path but the way of reality, we are not compelled to perform this contemplation [of death] in an imaginary and hypothetical form like the Sufis” [13].

Like Said Nursi, Gülen belongs to no tariqa and follows no pir. He explicitly rejects the idea that he is trying to found some new type of Sufi Order. He describes his complex relationship to the Sufi tradition as follows: “I have stated innumerable times that I’m not a member of a religious order. As a religion, Islam naturally emphasizes the spiritual realm. It takes the training of the ego as a basic principle. Asceticism, piety, kindness and sincerity are essential to it. In the history of Islam, the discipline that dwelt most on these matters was Sufism. Opposing this would be opposing the essence of Islam. But I repeat, just as I never joined a Sufi order, I have never had any relationship to one” [14].

Common concerns with the Sufi masters

On the other hand, Gülen shares many concerns with the exponents of the Sufi tradition and praises Said Nursi for “pouring down on us all the wealth of our schools and Sufi lodges (takka, zaviya, maktab, madrasa)” [15]. Like the Sufis, and like Said Nursi before him, he places the primacy in Islam on love, which he regards not only as a gift of the Creator God, but as the bond that unites humanity and can overcome disunity. “God Almighty has not created a stronger relation than love, this chain that binds humans one to another” [16]. Gülen’s theological vision focuses on many of the same themes founding the writings of the Sufi Masters. He elaborates, in the context of the demands of the Islamic community today, such typical Sufi concepts as ikhlas (sincerity or purity of intention), ma’rifat (knowledge), sabr (patience), and taqwa (piety).

Where Gülen’s theological vision departs from that of the Sufis is his emphasis on communitarian dimension of selfless service. While he affirms the importance of solitude and retreat (halwat) to purify one’s spirit, [17] he rejects any spirituality that supports an individualistic mystical flight to union with God that characterizes much Sufi theory and practice. He is similarly disinterested in the kind of metaphysical speculation that preoccupied so many of the Sufis.

For Gülen, spirituality must always be oriented towards service of God and of others. He states: “Individual projects of enlightenment that are not planned to aid the community are doomed to fruitlessness… Just as plans and projects for individual salvation that are independent of the salvation of others are nothing more than an illusion, so too, the thought of achieving success as a whole by paralyzing the individual awakening is a fantasy” [18].

The emphasis that he places on communitarian service of humanity is a quality that distinguishes the community inspired by the thought of Fethullah Gülen both from that of the Sufi practitioners and from that of the Nur cemaat who follow more strictly the teaching of Said Nursi. For Nursi, transformations of Islamic societies, and eventually civil societies, will come about through the personal transformation of the individual Muslim achieved through the study of the Risale-i Nur, Nursi’s 6000-page commentary on the Qur’an. While members of Gülen’s community also study the Risale-i Nur, Gülen hopes to bring about societal transformation through the establishment of institutions (e.g., schools, media instruments, dialogue centers) to promote the desired transformation. For Gülen, the way to God is by serving others. He states: “This path passes through the inescapable dimension of servanthood to God by means of serving first of all our families, relatives, and neighbors, then our country and nation, and finally humanity and creation” [19]. The community commonly refers to its activities simply as “The Service” (Hizmet).

Among the common concerns that Gülen shares with proponents of the Sufi tradition like Mevlana Jalal al-Din Rumi is the importance of concepts dealing with the “interiorization” of religious practice. In particular, he focuses on two of these Qur’anic elements, which can be said to form the conceptual basis of Gülen’s theology. These are the notion of ikhlas, which may be translated “purity of intention” or “sincerity,” and that of ‘ibada (worship), with its related concepts of ‘ubudiyya (servanthood) and ‘ubada (devotion).

Because of their centrality to the thought of Fethullah Gülen and the extent to which they shape and characterize the motivation and attitudes of the community inspired by his ideas, ikhlas and ‘ibada can be said to be the cornerstones or pillars of Gülen’s theology. I have written about the topic of ikhlas elsewhere, [20] but because the concept is so basic to Gülen’s theological perspective and so essential for the unity of Hizmet cemaat, I will take up once again key points of the topic in the next issue.

Notes

- Fethullah Gülen and those Muslims inspired by his thought dislike the terms “Gülen movement” and “Gülen community,” which imply that Gülen dictates and directs everything done by the community (cemaat in Turkish). They refer to the community’s activities as the Hizmet, “the Service.) However, since the former terms have entered both scholarly and popular usage, I will employ them in this paper.

- Fethullah Gülen, “Prophethood and Muhammad’s Prophethood,” in Essentials of the Islamic Faith, Somerset, NJ: Tughra Books, 2009, p. 163. (Originally published as İnancın Gölgesinde, Nil Yayınları, 1961)

- Fethullah Gülen, Muhammad the Messenger of God, Clifton, NJ: Tughra Books, 2010, p. 327.

- Fethullah Gülen, Speech to Visiting Scholars, 13 January 1996. Reprinted in Toward a Global Civilization of Love and Tolerance, Somerset, NJ: The Light, p. 82.

- , p. 163. Cf. my analysis of Gülen’s appropriation of these figures in “Fethullah Gülen: Following in the Footsteps of Rumi,” in Peaceful Coexistence: Fethullah Gülen’s Initiatives in the Contemporary World, London: Leeds Metropolitan University Press, 2007, pp. 183-191.

- More than any other individual, Rumi seems to epitomize for Gülen the characteristics he seeks to form in modern Muslims. “They call everyone to their embrace and to the truth, like Mawlana Jalal al-Din Rumi, and they tolerate every improper behavior toward themselves.” M. Fethullah Gülen, Key Concepts in the Practice of Sufism: Emerald Hills of the Heart, Somerset: NJ: 2009, III: 270.

- Fethullah Gülen, The Statue of Our Souls: Revival in Islamic Thought and Activism, Somerset, NJ: 2009, pp. 68-72.

- Rıfat Atay, “Reviving the Suffa Tradition,” in Muslim World in Transition: Contribution of the Gülen Movement, London: Leeds Metropolitan U.P., 2007, pp. 459-472.

- Zeki Saritoprak, “Fethullah Gülen: A Sufi in His Own Way,” Turkish Islam and the Secular State, Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003, pp. 156-169.

- Thomas Michel, “Der türkische Islam im Dialog mit der modernen Gesellschaft. Die neo-sufistische Spiritualität der Gülen-Bewegung,” Concilium, Dezember, 2005. See also, “Sufism and Modernity in the Thought of Fethullah Gülen,” The Muslim World, 95/3: 2005, pp. 341-353.

- Mustafa Gökçek, “Fethullah Gülen and Sufism: a Historical Perspective,” Muslim Citizens of the Globalized World: Contributions of the Gülen Movement, pp. 183-193.

- Fethullah Gülen, Key concepts in the Practice of Sufism: Emerald Hills of the Heart, Vols. I-IV, Somerset, NJ: Tughra Books, 2009-2010.

- Said Nursi, Risale-i Nur, Twenty-first Flash, p. 217.

- Fethullah Gülen, cited in Lynne Emily Webb, Fethullah Gülen: Is There More to Him than Meets the Eye?, Paterson, N.J.: Zinnur Book, n.d., p. 80.

- Fethullah Gülen, The Statue of Our Souls: Revival in Islamic Thought and Activism, p. 77.

- Fethullah Gülen, The Horizon, Istanbul: Nil, 2000, p. 34. Reprinted in Toward a Global Civilization of Love and Tolerance, p. 37.

- Gülen, Key Concepts in the Practice of Sufism, III: 27.

- Fethullah Gülen, The Horizon, Istanbul: Nil, 2000, p. 192. Reprinted in Toward a Global Civilization of Love and Tolerance, p. 62.

- Fethullah Gülen, Essays – Perspectives – Opinions, Somerset NJ: The Light, 2002, p. 90.

- I delivered a paper entitled “The Wing of the Bird: Gülen on Sincerity” at an academic congress on the thought of M.F. Gülen held in Potsdam, Germany, in May, 2009, and a revised version of the paper at a similar congress held in Munich, Germany in February, 2010. The paper has been published in German in CIBEDO Beiträge, (Frankfurt, 3/2009) as “Der Flügel des Vogels: Gülen über Aufrichtigkeit (Frankfurt, 3/2009), pp. 99-102.